Overview

Over the past 30 years, the effects of AIDS have included a staggering 60 million infections and 30 million deaths (Hammer, 2011). AIDS has taken a particular toll on women. Women now make up sixty percent of those living with HIV in Africa and 50% of those living with HIV globally (UNAIDS, 2011a; UNAIDS, 2011b) and HIV is still the leading killer of women of reproductive age worldwide (Girard et al., 2010; UNAIDS, 2011a). Women's and girls' vulnerability to HIV infection stems from a greater biological risk that is compounded by gender inequalities, violations of women's human rights, including violence, and, for some women, criminalization and marginalization.

"Despite the many challenges in reducing HIV infection in women, there are numerous opportunities to effectively act on now." (Abdool Karim et al., 2010a: S127)Analysis from 20 countries in sub-Saharan Africa found that women have 68% higher odds of HIV infection than their male counterparts of similar socioeconomic background and sexual behavior (Magadi, 2011). Further evidence is needed to explain the reasons for women's increased risk of infection, given that studies to investigate likely causes of breeches in the natural defense mechanisms in the female genital tract such as those due to breaks in the epithelial lining following douching, sexual intercourse, cervical ectopy with combined oral contraceptive use and cell changes from HPV have been inadequate to explain the excess burden of HIV in women (Abdool Karim et al., 2010a). Structural factors such as gender norms, legal rights, stigma and other social and economic issues must also be further explored.

The impact of the HIV/AIDS epidemic among women and girls has not gone unnoticed. Numerous international political declarations have recognized women's and girls' specific risks and needs and have committed to act to address them. Multilateral and bilateral donors have established strategies to better address women, girls, gender equality and HIV/AIDS and a number of countries have developed national action plans. However, the funding and implementation of evidence-based programs for women and girls continue to lag (UN General Assembly, 2011).

There is an urgent need to develop and scale up strategies to address the needs of women and girls in the global AIDS response and support women as agents of change. The UNAIDS Agenda for Accelerated Country Action for Women, Girls, Gender Equality and HIV calls for "evidence-informed policies, programmes and resource-allocations that respond to the needs of women and girls..." (UNAIDS, 2010f: v). This focus on women can be done in the context of the call to "accelerate the implementation of the many currently available evidence-based HIV treatment and prevention tools" (Dieffenbach and Fauci, 2011: 1). At the same time, after 30 years, a transition is needed from an emergency response to a public health approach that is more integrated within health systems and more durable and sustainable (Atun and Bataringaya, 2011). Furthermore, in this era of budget constraints, programs must focus on effectiveness and efficiency in programming. "Policy makers must prioritize interventions that maximize impact while staying within budget constraints" (Menzies et al., 2009: 396). At the same time, approaches must be equitable, ensuring inclusion, participation, informed consent and accountability (Schwartlander et al., 2011).

"Success depends on deploying our tools based on the best available evidence." -Hillary Clinton (Clinton, 2011)The purpose of What Works for Women and Girls: Evidence for HIV/AIDS Interventions is to provide the evidence necessary to inform country-level programming. What Works for Women and Girls: Evidence for Effective HIV/AIDS Interventions contributes to this effort. What Works is a comprehensive review, spanning 2,500 articles and reports with data close to 100 countries, that has uncovered a number of interventions for which there is substantial evidence of success: from prevention, treatment, care and support to strengthening the enabling environment for policies and programming. What Works also highlights a number of gaps in programming that remain.

International Political Commitments on Women, Girls and HIV/AIDS

At the United Nations General Assembly Special Session in 2001, governments noted that "women and girls are disproportionately affected by HIV/AIDS" and committed to develop national strategies to "promote the advancement of women and women's full enjoyment of all human rights; promote shared responsibility of men and women to ensure safe sex; empower women to have control over and decide freely and responsibly on matters related to their sexuality to increase their ability to protect themselves from HIV infection" (UN General Assembly, 2001). In 2006, member states of the United Nations General Assembly went further in the Political Declaration on HIV/AIDS, committing themselves to, among other things:

- Promote responsible sexual behavior among youth and adolescents (including the use of condoms);

- Provide evidence- and skills-based, youth-specific HIV education and mass media interventions;

- Provide youth-friendly health services;

- Eliminate gender inequalities, gender-based abuse and violence;

- Provide health care and services, including for sexual and reproductive health, as well as comprehensive information and education to increase the capacity of women and adolescent girls to protect themselves from the risk of HIV infection;

- Ensure that women can exercise their right to have control over, and decide freely and responsibly on, matters related to their sexuality in order to increase their ability to protect themselves from HIV infection;

- Take all necessary measures to create an enabling environment for the empowerment of women and strengthen their economic independence;

- Strengthen legal, policy, administrative and other measures for the promotion and protection of women's full enjoyment of all human rights;

- Ensure that pregnant women have access to antenatal care, information, counseling and other HIV services;

- Increase the availability of and access to effective treatment to women living with HIV and infants in order to reduce mother-to-child transmission of HIV;

- Ensure effective interventions for women living with HIV, including voluntary and confidential counseling and testing, with informed consent; access to treatment, especially lifelong antiretroviral therapy; and the provision of a continuum of care.

Global Initiatives on Women, Girls and HIV/AIDS: Strong Promise with Challenges

A number of multilateral and bilateral donors have developed gender policies or strategies. The legislation authorizing the U.S. President's Initiative for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) contained strong language related to gender and the need to address the vulnerability of women and girls with strong programming to reduce gender inequity (Ashburn et al., 2009; USAID/AIDSTAR-One, 2009). The Office of the Global AIDS Coordinator (OGAC) defined five strategies to address gender inequity, including:

- Increasing gender equity in HIV/AIDS activities and services;

- Reducing violence and coercion;

- Addressing male norms and behaviors;

- Increasing women's legal protection; and

- Increasing women's access to income and productive resources.

These strategies continue to shape programming under the reauthorization of PEPFAR in 2008 (PEPFAR, ND).

The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (Global Fund) also has a Gender Equality Strategy (GES), approved in late 2008 (Global Fund, 2009), which is aligned with the principles underpinning the Global Fund's approach: country-led initiatives; evidence-based practices; subject to independent review; and able to be monitored. Based on the GES, the Global Fund promotes programs and seeks proposals that:

- Scale up services and interventions that reduce gender-related risks and vulnerabilities to infection;

- Decrease the burden of disease for those most at-risk;

- Mitigate the impact of the three diseases; and

- Address structural inequalities and discrimination.

Analysis of gender-related activities in HIV proposals in Round 10 proposals to the Global Fund found that despite a positive trend over rounds 8 and 9, several challenges remain, namely, "weak data analysis and disaggregation by gender (particularly marginalized women), the partial application of the comprehensive four pronged PMTCT approach, and the lack of integrated and comprehensive approaches to address gender-based violence" (Global Fund, 2011a: 2). An evaluation in 2011 found that the Gender Equality Strategy had been less influential in guiding Global Fund programming than the Sexual Orientation and Gender Identities Strategy (SOGI). On the basis of these findings, the Global Fund has determined that its "gender equality and SOGI work will now move forward in the context of the new strategy for 2012-2016, consistent with its objectives of investing more strategically for impact and promoting and protecting human rights" (Global Fund, 2011b: 4).

National Strategies Have Been Developed But Implementation Is Lagging

Some countries have also created agendas that address gender issues within the AIDS pandemic. For example, Brazil brought together government agencies, the Ministry of Health and the Special Secretary for Women's Policies, along with leaders in women's rights and health promotion to develop an intersectoral policy to address womens needs in the AIDS pandemic such as access to health services; sexual and reproductive health care; social service needs (Guimaraes de Andrade et al., 2008). Similarly, seven Southern African countries have established national action plans on women, girls and HIV with multi-stakeholder involvement (UNAIDS, 2007c). Analysis of the National Composite Policy Index from 130 countries of progress in creating an enabling policy environment for women suggests that policies and strategic plans are integrating women-related issues, but that funding for implementation is lagging (Carael et al., 2009). For example, only 46% of countries reporting to UNAIDS had a specific budget for HIV activities related to women (UNAIDS, 2010a: 132).

What Works Provides Evidence to Inform Programming

One reason for the lag in program implementation is the lack of easily accessible information on which strategies are most effective in addressing women's and girls' HIV prevention, treatment, care and support needs. What Work for Women and Girls: Evidence for HIV/AIDS Interventions compiles the evidence available to support successful interventions for HIV and malaria and hepatitis as they relate to HIV and AIDS.

...This document serves the unique function of bringing all of these topics together to provide a full range of gender-sensitive programming for women and girls.

What Works aims to make evidence on interventions available in one place. Policymakers have limited resources for reviewing the evidence base to inform policies and programs (Lavis et al., 2009). What Works is an effort to provide policymakers with an easy to search database on the evidence base on women and HIV. "Improving the flow of evidence between global health researchers and policymakers is an important tool for improving health outcomes" (Yamey and Feachem, 2011: 97). Furthermore, making evidence easily accessible should speed the uptake of evidence for policies and programs. A review of nine landmark clinical procedures found that, on average, it takes a minimum of 6 years for research evidence to reach textbooks; and an additional 9 years to implement the evidence from scientific publications (Dickson et al., 2011). Given the seriousness of the AIDS pandemic, What Works should facilitate shortening the interval between generating evidence and implementation.

Clearly, the question of "what works," is complex. In designing HIV and AIDS programs, policymakers and program planners are faced with a wide array of interventions. With scarce resources and growing demand for services, program priorities must be based on effective interventions. Most scientific and biomedical research on HIV and AIDS interventions has been written for scientists; little has been written specifically for policymakers, practitioners and engaged communities.

This material is intended for practitioners who are designing HIV and AIDS interventions meant to address the needs of women and girls, and who are deciding among priority interventions. It is also intended for engaged communities advocating for programming (Delany-Moretlwe et al., 2011). Organizations that provide assistance to programs worldwide will also benefit from this evidence. www.whatworksforwomen.org can be used by bilateral and multilateral donors, development banks, foundations, governmental officials, and nongovernmental organizations. It can be used for programming in both low- and middle-income countries alike (Hecht et al., 2010; UNAIDS, 2011a).

This evidence was obtained primarily through detailed searches of peer-reviewed publications documenting evaluated interventions for women and girls. In all, the evidence for What Works and Promising interventions includes 641 studies. [See Methodology]

There are obvious limitations inherent in this approach: many worthwhile interventions do not have sex-disaggregated data. A review of 34,000 abstracts from 2003 to 2009 from the International AIDS Conference (IAC), the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI) and the Canadian Association of HIV Research, found that only 16% of the abstracts were women-specific (Lunny et al., 2011). Many interventions are not thoroughly evaluated and still others are not published in peer-reviewed journals or are not published at all. While this review covers many aspects of HIV/AIDS programming that are relevant for both women and men, it is not intended to be an exhaustive review of all HIV/AIDS programming. Instead, the review focuses on interventions that have an impact on HIV outcomes for women and girls.

This resource is also not meant to be a set of guidelines for gender-sensitive programming, as it does not cover what should be done; instead it documents practices for which there is evidence of successful approaches. This compendium is best used with the range of guidelines for programming and it highlights some of those guidelines. Ideally, this resource will serve to spur more programmers to evaluate their successful approaches and add them to the lexicon of "what works," as well as to encourage researchers to set research agendas based on areas that are clear and critical gaps for women and girls.

Scaling Up of Effective Interventions for Women and Girls Is Needed

The interventions highlighted in this compendium are, for the most part, implemented on a small scale. Scant information is available on the costs of the interventions. It will be important to scale up the interventions to reach a broad range of relevant women and girls. In determining the feasibility of scaling up, it is important to assess the geographic coverage of the intervention, how gender was integrated and how well the intervention linked to a broader program strategy. How many countries were included? What populations/contexts within countries were included? Are any data regional, national or cross-national in scale? How well was gender integrated from conceptualization through implementation to evaluation? Was a gender analysis conducted to guide development of the program (Greene, 2012a)? Can the evidence be linked to a program strategy? It is also important to assess whether:

- Political support and buy-in for broad-scale implementation can be secured;

- Wider standards could be developed from the pilot or smaller-scale intervention;

- The intervention could be integrated into the public health system;

- Gender analysis in the broader program context is conducted and the intervention can be implemented given existing gender and epidemiology contexts;

- The intervention would have wide acceptability;

- Strategies can be devised to ensure acceptability;

- Information is available on the costs of the interventions;

- Interventions identified as "what works," will need to be adapted to local contexts and needs;

- Implementation of successful interventions for women and girls must also always respect their human rights.

Organization of this Resource

This compendium covers the evidence for gender-sensitive programming for women and girls. The chapters are organized under three broad sections: what works to prevent infection, including in women, young women and women with special prevention needs, such as sex workers and women who use drugs and female partners of men who use drugs; what works for women and girls living with HIV, such as treatment, meeting sexual and reproductive health needs, and preventing vertical transmission; and what works to support women and girls, including strengthening the enabling environment through, among other things, addressing gender norms, violence against women and stigma and discrimination and promoting womens legal rights and access to education and livelihoods. Supporting women and girls also includes providing care and support, OVC programs and structuring health services to meet womens needs.

Each chapter in the compendium includes an introduction, followed by a list of interventions that work or are promising followed by the evidence to support the interventions and the remaining gaps in research, programming or evaluation. The compendium also includes a selection of the most recent clinical manuals and resources for program design, and references (citations for each study and web sites, where possible). In some areas, the evidence is quite limited because few evaluations have been conducted. The Gaps sections of the compendium are important because they include a number of expert recommendations or recommended interventions based on studies measuring knowledge or attitudes that are expected to work but have not been formally evaluated.

This resource serves the unique function of bringing all of these topics together to provide a full range of gender sensitive programming for women and girls. It is very important to note that each of these chapters addresses topics that, themselves, could be the focus of multiple books. The authors have endeavored to cover the major evidence in each of these areas about what works for women; however, more nuanced information about these topics can be found in the myriad references and websites devoted to them, some of which are referenced in this resource.

The resource is not designed to provide complete recommendations on program design for particular topics, but rather serves the unique function of bringing the evidence for all of these topics together to provide a fuller picture of the range of gender-sensitive programming for women and girls.

Scope of the Evidence

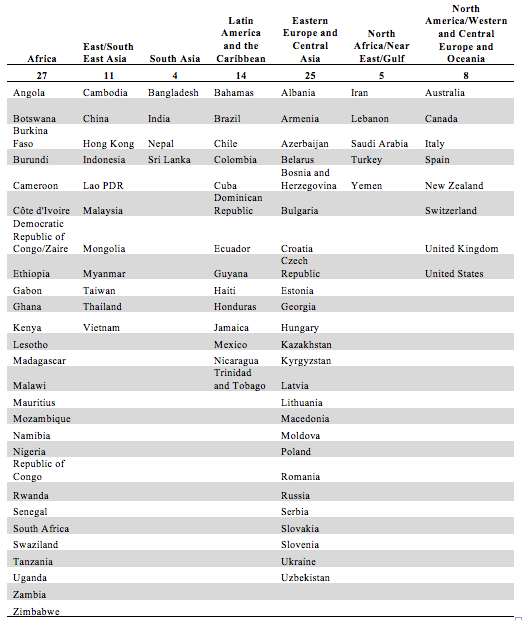

This compendium includes over 2,000 references from programs and studies in 94 countries, including 27 in sub-Saharan Africa, 11 from East and South East Asia, 4 from South Asia, 14 from Latin America and the Caribbean, 25 from Eastern Europe and Central Asia, five from North Africa and the Near East and 8 from North America, Western and Central Europe and Oceania. Among these countries, the countries generating the most evidence include Uganda and South Africa. In addition, data from a number of additional countries are included in introductions to chapters and sections and in the gaps.

Countries included in What Works (N=94)